Courtesy Apple Maps

This website uses cookies to enhance usability and provide you with a more personal experience. By using this website, you agree to our use of cookies as explained in our Privacy Policy.

Beside the Jordan River Parkway Trail, the Galena–Soo’nkahni Monument honors the ancient and continuing presence of diverse Indigenous peoples across Utah.

The monument forms a walkable sundial. Its pillars inform visitors about Utah’s eight sovereign Native Nations, whose ancestral connections to the Intermountain region are thousands of years old and deep. One of the oldest Indigenous sites to be found in this region is now protected by the Galena–Soo’nkahni Preserve, which forms part of the Jordan River Parkway conservation area.

Over 3,000 years ago Native Americans established a small village next to the Jordan River, in what is now Draper. The site had notable advantages: the Jordan River corridor connecting Utah Lake and Great Salt Lake offered reliable water. Its wetlands and riparian areas supported over 200 species of birds and abundant game ranging from deer to rodents and fish. Thick stands of river willow and meadow grasses provided essential plant foods, along with raw materials for shelters, clothing, baskets, and other useful items. From high ground overlooking the river, views of the valley stretch for miles in every direction, offering a strategic vantage point.

Based on radiocarbon dating, food remains, and material culture, archaeologists concluded this place served as a winter village for more than 1,700 years: from about 1,000 BC until 700 AD. While this is one of the oldest Native American villages to be documented in the Salt Lake Valley, Indigenous oral traditions indicate that Native people have lived in these lands for over 13,000 years, their ancestral presence stretching back into time immemorial. By way of comparison, immigrants settled the city we know as Draper in 1852. Draper is less than 200 years old.

This village was comprised of pit houses—small homes dug partially into the ground about 60 cm deep. A domed roof made of limbs and branches completed the shelter. The homes had hearths inside for a fire, and there was room for a small family to sleep. This type of home was characteristic of long-term villages in the Archaic Period. During the warmer months, Indigenous families moved around the region strategically to harvest a variety of plant foods as they came into season. They returned to spend the winter months here.

The people who lived here used a wide range of tools made of bone and stone. They used a spear thrower called an atl-atl to hunt large game such as deer and pronghorn. They used mano and metate stones to grind roots, seeds, and maize into meal, which could be boiled into porridge or made into cakes.

The villagers also made a large roasting pit. Pit roasting is a common cooking technique across much of the world, in which people heat hot rocks to line the bottom of the pit, add water, then cover the pit to steam or roast a variety of foods. Typical foods in this area included meats, fish, pinyon nuts, grass seeds, cattail roots, and berries. Plant foods, then as now, could only be harvested seasonally, so were gathered and stored in baskets and ceramics for winter.

Archaeologists found compelling evidence of maize, beans, and possibly squashes in this village, at a time before these crops were commonly grown in this region. The adoption of these crops, which moved north from Mexico throughout North America, marked a shift in Native food economies that characterizes what archaeologists named the Fremont Period (500 BC–1250 AD). The presence of maize in this village suggests these crops may have been adopted much earlier in this area.

Native Americans have lived along the Wasatch Front from at least the Archaic Period, as documented in this site, through the present day. Throughout the centuries, the people lived in locations such as this one—near reliable water in the temperate valleys—and harvested resources across extended territories.

At the time of settlement in the mid-19th century, Draper was part of an area shared by Western Ute, Northwestern Shoshone, and Goshute people. Utah Valley was a population center for the Timpanogos Utes, Goshutes lived just to the west in Tooele Valley, and Shoshones lived from Salt Lake City north.

Today, Native Americans make up roughly 2.7% of Utah’s population overall, and 2.3% of the total population living along the Wasatch Front.

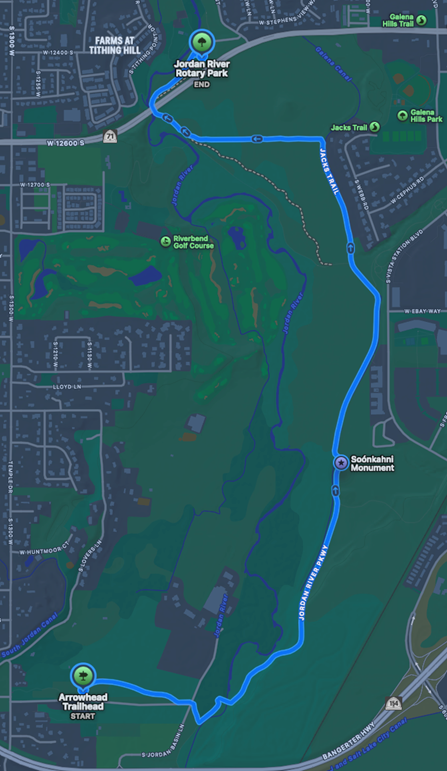

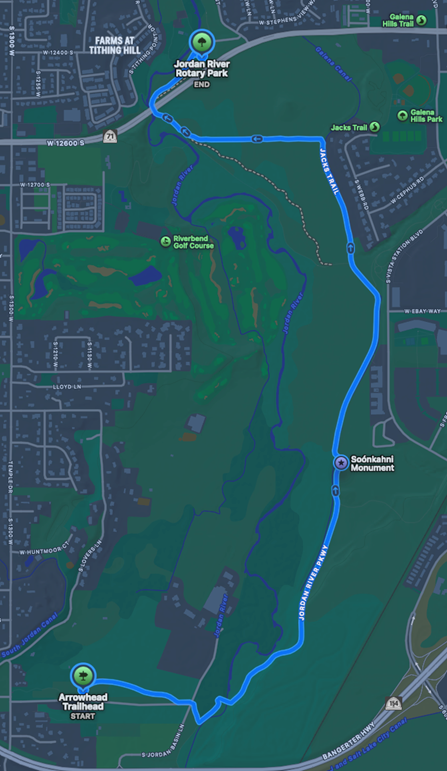

Visit the Monument:

There is no parking at the monument. Walk or bike on the Jordan River Parkway Trail from these access points:

Courtesy Apple Maps

Native American Ancestral Homelands – map (BYU ARTS Partnership)

Utah Native Place Names Interactive Atlas – map (American West Center, UofU)

Utah Division of Indian Affairs

The Utah State Historic Preservation Office coordinates a Cultural Site Stewardship program, which allows local volunteers to monitor and help protect archaeological sites from vandalism and looting. Learn more and get involved here: https://ushpo.utah.gov/shpo/archaeology-2/ucss/